I can no longer feel the top of my head. Apparently it takes 3-5 months to regain sensation up there, and some people never get the feeling back. Oh well, what do you need to feel things from the top of your head for anyway?

But, it’s truly bizarre touching the top of my head and only getting feedback from my hand. Almost like touching someone else’s head except my brain knows where my hand is and seems to get confused, as if it doesn’t know how to close the loop. Proof I guess of just how connected the body and the mind are.

Anyway, you probably want to know, what’s its like? What does it feel like to be awake while someone is drilling deep inside your skull? Well, let me walk you through it as best as I can.

The day began by getting this lovely looking frame bolted on. It didn’t feel as bad as it looks. They froze the areas where the bolts go so other than the weight and some added pressure around my skull I didn’t really feel it. But, after they turned me into a cartoon supervillain, I learned that an emergency case had come in that would delay my surgery by an hour or two. So, I sat there in the cramped pre-op room staring at the other patients who were doing their best not to look horrified when we made eye contact.

Eventually I got wheeled into the OR. Like a guest of honor there were many onlookers waiting for me when I arrived. In addition to the surgical team itself of at least 7 or 8 people, there were a couple rows of students who had come to watch and learn.

First I was laid out on the table and had that frame locked into a much larger contraption that would keep my head securely in place no matter how much I wriggled and writhed about. Then there was about half an hour of prep the team did in a flurry of activity happening all around me. During which time my hair was cut, but only the parts that might get in the way of the procedure, giving me that classically handsome friar tuck look. Then all sorts of sterilizing ointments were applied. Between that, the oxygen, and the mild sedatives I was given it was almost starting to feel like a trip to a spa.

Almost.

Throughout the morning I had felt very ready for what I was about to experience. I’m not sure exactly what to attribute that to, but in the days preceding it my mind was completely at ease with what I was about to experience. One fear I thought I might have going in was that I would start to doubt the decision I had made. As I’ve written , DBS was not the only option available to me. What if I got into the OR and started to second guess myself?

Thankfully I never paid the thought much attention. Part of it was that I knew I was in great hands, Dr. Suneil Kalia and his team at Toronto Western Hospital are as good as it gets. It also helped that I knew I had done my homework.

Four years earlier on a Friday morning in Jerusalem I was wandering the halls of Hadassah medical center looking for Prof. Hagai Bergman. Friday is the start of Shabbat, the day of rest when all of Jerusalem shuts down. I wandered through the empty halls of his building wondering if I had come at the wrong time, but there he was, and he seemed anxious to see me.

He ushered me into his office and spent the next three hours taking me on a guided private tour of the basal ganglia as well as a new therapy that he was helping make a reality – closed loop deep brain stimulation. I didn’t realize it at the time but he was showing me my future.

He also recommended to me a pair of books, The Mind’s I and I Am A Strange Loop by Douglas Hofstadter. I’ve had them close to me ever since and often return to them. I haven’t read anything else that comes as close to explaining who and what we are, why we experience what we experience, and why we think the thoughts that we think. Some say we have no idea how DBS, or the brain for that matter, work. But, if closed loop DBS is successful, I think it would prove that while we may not ever know all the details, we do some of the right conceptual frameworks in place. We are a collection of strange loops and most of the neurological problems we face can be attributed to a break in one or more of those loops. Find the right loop or loops to close and we can fix just about anything that goes wrong.

I haven’t spoken to Prof. Bergman since, but will forever be grateful for those three hours he spent patiently explaining this new technique that I will soon be turning on inside my own head to me. Here is a taste of that lecture he gave me.

I’ll have much more to say on closed loop DBS in the future. Back to the OR.

Now, as much as I believed I was ready for what I was about to experience, nothing can really prepare you for what it is like to be awake during it all. Every detail of that morning has been indelibly etched into my memory, yet I struggle to find the words to describe it. Language isn’t really suited for such things and whatever words I’ll choose to use probably won’t really be able to capture it. Such is life I guess.

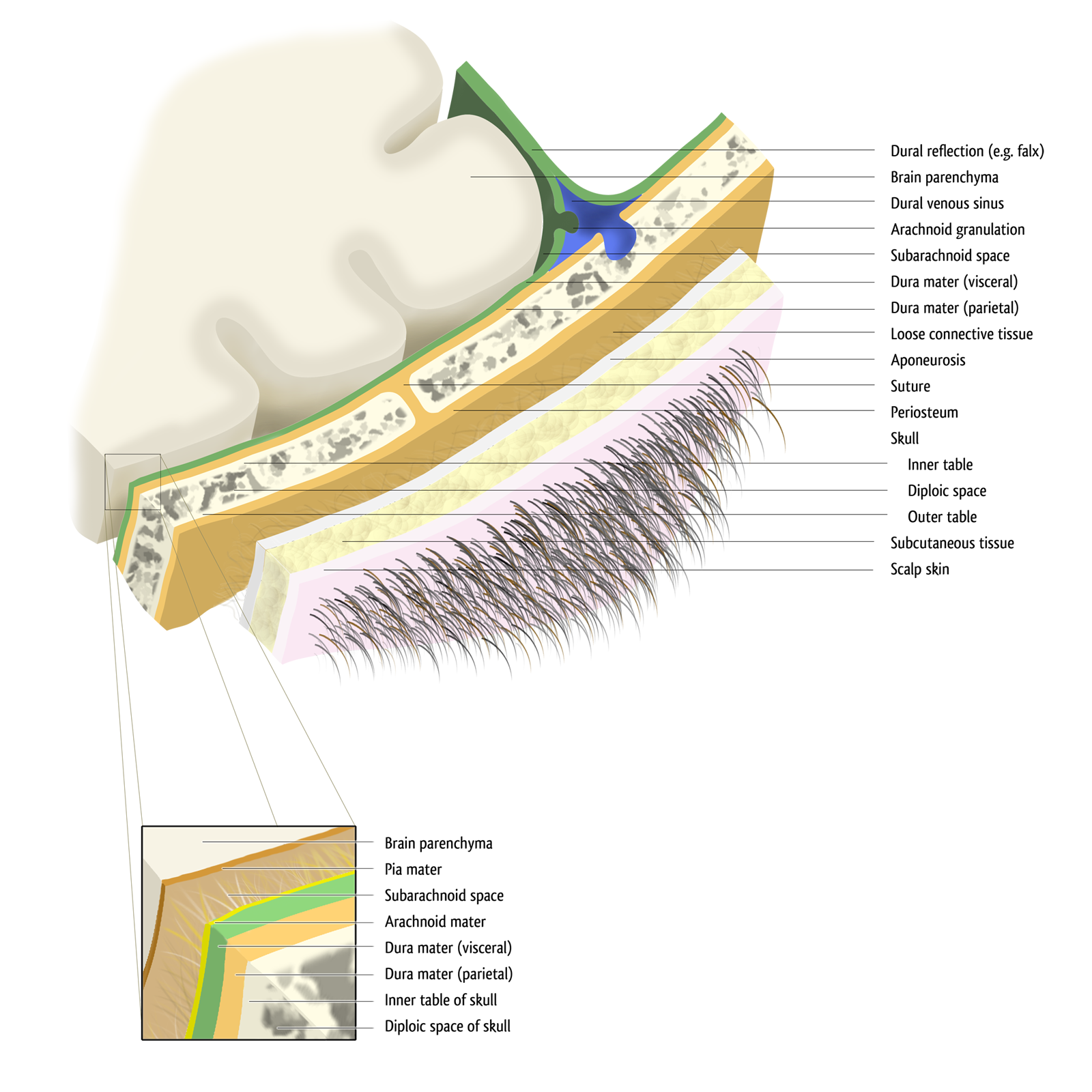

I’ll start with the pain, which there really isn’t that much of. The only thing that really really hurt were all the needles used to freeze my scalp, after that I didn’t really feel anything. So I was a little surprised when after the freezing they told me that they were ready to start drilling through my skull, meaning they had already sliced through all the various layers of my scalp.

Next came the drilling of the bore holes. If there is any part of this procedure that is likely to induce trauma it is this. I will never forget that sound. Usually sound is created by your ear picking up tiny vibrations of particles in the air. But in this case the sound came more from my entire skull shaking violently to the rotating drill boring a hole through my head. I didn’t hear it as much as I felt it, as if the entire universe was grinding together inside my skull.

Once my brain was exposed the team covered themselves and me in protective gear so they could turn on the stereotactic imaging device that guides the surgeon through my brain deep into my subthalamic nucleus. All of that was displayed on a screen in front of me allowing myself and the team to see what was happening. This went by surprisingly quickly and was somewhat uneventful, though I do remembered some murmured remarks between the surgeons about avoiding a particular vein somewhere along the way.

I did wonder, what would it be like if something went wrong. What would the reactions of the surgeons have been if they tripped that vein? All through the procedure the team sounded very calm and business like. Would the tone of their words suddenly have turned to panic? And what would I experience? Would the world suddenly go dark? Would my conscious awareness and this chain of experience I call my self suddenly shift to something else?

Anyway, once it looked like it was in the right spot, which you can tell by the lead penetrating the crosshairs on the screen, they began the microelectrode recording. They played the live sound on a speaker which emitted the different noises of each cortical layer as it went deeper and deeper. Throughout the procedure I was talking and lucid. Lobbing question after question at the team, here Dr. Kalia had to tell me to shut up so they could listen and confirm they were in the right spot.

The crescendo slowly built until it reached the target and then the sound of hundreds of thousands of my own neurons excitedly relaying the information they carry to one another filled the room. My brain was speaking to me, though in a language “I” could not understand. And even though I knew there was some perturbation in that sound that was responsible for the symptoms I felt, I smiled thinking of all that was going right inside me.

Once they confirmed they were in the desired position the stimulation was turned on. It was in the left hemisphere of my brain which controls the right side of my body. I was asked to do a few simple movement tasks with my hands like tapping my index finger and thumb together as quickly and as wide as possible and pretending to turn a doorknob. It was roughly noon and because of the surgery I had not taken any medication up to that point. Normally if I had gone until noon without any medication I would have had a pronounced tremor, the tapping would have quickly become slow and labored, and I would have barely been able to turn my wrist over and back. But at that moment I felt I had travelled back in time eight years to before my diagnosis. My fingers and my wrist moved fluidly. It was liberating, I was back in control. Despite being strapped to a table with my head in a vice I felt euphoric. This disease had suddenly and magically dissipated. Nothing short of a modern medical miracle.

But it was short lived as I was then reminded that the entire process needed to be repeated for the other side. Now the novelty of the whole experience wore off and I started to really feel the weight of the frame tying me down. I closed my eyes, gritted my teeth and got through it. But not without the whole thing taking its toll. A mix of nausea and a shearing headache crept over me that slowly grew in intensity. I wanted to tell them not to bother with getting this side as precise as possible, to just hurry up and get it all over with as quickly as they could.

There is a lot more I could say about the whole ordeal, including the tunneling of the wires through my neck and the placement of the battery in my chest two days later, but I’ll leave it at that for now. It has been 12 days since the operation and I am feeling much better than I would have expected, though not entirely like myself either. In less than a month I should begin programming the device which hopefully will make everything I experienced worthwhile. I’m not sure exactly what I’ll do if, once we get all the parameters right, they flick that switch and I get to permanently return to that state I felt when they turned on the stimulation in the OR, but suffice it to say that I am looking forward to getting there.

The last thing I’ll show is the MRI I had taken the day after. The white dots you see on the left is the inflammation surrounding the holes that were drilled. I close my eyes and wonder how all the cells surrounding that spot must be reacting, all the neurons trying to communicate with this foreign object, all the glial cells now busily forming the scar tissue that will lock those long leads you see on the right in place for the rest of my life.

In a few weeks, the stimulator will be turned on and the contacts will be activated, hopefully restoring mobility to this strange loop that I am.

You are an inspiration

I am very pleased that your operation appears to have gone welll; You will be looking foreward to switching it on no doubt.

Keith

Amazing to hear what your experience was like… Keep us posted!

As usual. Great post! You are an inspiration and good luck turning on the juice soon, best wishes, Frank

This was a fascinating post to read as a neurosurgery resident. Thank you for sharing your experience, and I hope DBS works out for you.

The human body is an incredible, complex, designed piece of artistry. May you go forth with renewed joy and gratefulness for this wonderful second chance of life.

Wild. we are so grateful to know you and see what you’re doing on your life’s journey. ♥️

You are amazing already writing so eloquently what happened to you during the surgery.

May all go as well as you wish for. Looking forward to learning more about your experience.

Ben, thank you for sharing your experience with DBS surgery and encouraging others to consider it. I hope it is a big help for your Parkinson’s symptoms.

Hello Benjamin, I can now see what my mother went through when she went through this surgery 3 months back. Thank you for writing up your experience. I wish you speedy recovery. All the very best

you are an inspiration. best wishes~

In 2017 I had a burr hole procedure done as part of an experimental clinical trial. It was interesting that you described the steps exactly as they occupied. In my case, evidently they didn’t numb the frame mounting locations enough because that is what hurt the most. The drilling although it sounds tramamatic was totally painless.